Modern moral discourse increasingly treats recognition as action. We are taught that naming injustice is equivalent to refusing its benefits, that acknowledgment absolves participation, that awareness substitutes for consequence. This error is not new. It is ancient.

Billie Eilish brought this pattern into focus during the 2026 Grammy Awards, when she declared, “No one is illegal on stolen land.” The statement was condemned by some as hypocritical and predictably defended by others as courageous truth-telling. But both responses missed the more important issue. This is not hypocrisy in the ordinary sense of knowing better and acting otherwise. It is something more dangerous: structural blindness.

Billie Eilish is worth tens of millions of dollars. She owns a multimillion-dollar home in Los Angeles. She profits from American entertainment infrastructure, American legal protections, American commercial distribution networks. She makes her declaration from a stage built on the very land she calls stolen, protected by security paid for with wealth generated by the system she claims is illegitimate. And then she goes home. To the house. On the land. That she keeps.

The problem is not just her moral hypocrisy, that she fails to live up to her stated values. The problem is that the declaration itself mistakes acknowledgment for consequence. The structure remains intact. The benefits are retained. The performance of moral awareness substitutes for action.

The Greeks had a word for this. They called it hubris.

In modern usage, hubris has been flattened into a synonym for arrogance or excessive pride. In Greek thought, it meant something more precise. Hubris is the failure to recognize the structure you inhabit. Acting as though the boundaries that constrain others do not apply to you. It is mistaking your position within an order for transcendence of that order.

Oeneus, king of Calydon, made offerings to the gods and forgot Artemis. Not out of malice. Out of carelessness. The omission was structural. The divine economy required reciprocity, and forgetting was never neutral. Artemis responded by sending a boar that ravaged the land. The kingdom collapsed not because enemies attacked, but because the king failed to recognize the structure he was operating within.

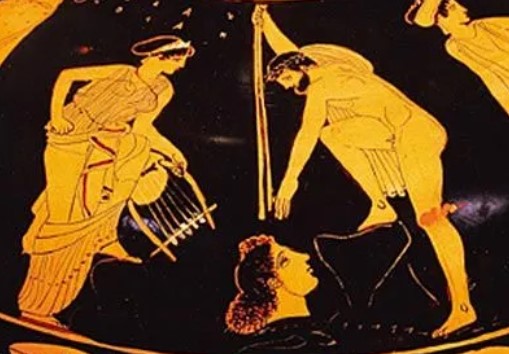

Theseus unified Attica, killed the Minotaur, and became king of Athens. He then abducted women. First the Amazon queen Antiope, then Helen of Sparta while she was still a child. This behavior had once been heroic license in a half-wild world. In an era of city-states, alliances, and laws, it became political crime. Theseus failed to recognize that he had transitioned from monster-slayer to civic ruler. The Dioscuri invaded Attica, retrieved Helen, and took Theseus’s mother as recompense. Athens did not defend him. The structure reasserted itself.

Tydeus, mortally wounded at Thebes, was offered immortality by Athena. In his final moments he tore open his enemy’s skull and ate the brains. Violence was not the problem. Violence was structural to the heroic age. What Athena could not tolerate was the celebration of savagery; the collapse of the boundary between hero and beast. Tydeus crossed the limen. He violated the threshold that separates sanctioned violence from monstrosity, the boundary that, as Arnold van Gennep showed, governs all rites of passage. The offer was withdrawn. Immortality was not denied as punishment. It was rescinded as disqualification.

In each case, the failure is not moral but structural. The punishment follows not because the act is evil, but because it violates the architecture of the world. The Greeks understood this with clinical precision. There are boundaries. They are real. Crossing them extracts costs whether or not you acknowledge them.

This is why Billie Eilish’s declaration matters. Not because she is uniquely wrong, but because her statement exemplifies a dominant modern pattern. The land is acknowledged as stolen. No move is made to return it. She could take an action that meaningfully alters her position within the structure she condemns. She will not. None of the moralizing elites will.

What persists instead is a secularized moral economy descended from Christianity, one that has retained confession while abandoning repentance. Friedrich Nietzsche diagnosed this transformation with unnerving clarity. Christianity inverted responsibility: guilt became interior, symbolic, endlessly verbal, while restitution and consequence were deferred or displaced. When God receded, the structure remained. Sin survived without redemption, and confession survived without cost.

The Greek gods did not absolve. They did not care about awareness. They enforced boundaries. Cross them, and consequence followed. Not as moral judgment, but as structural response.

What makes Greek myth remarkable, nearly unique among ancient traditions, is its refusal to sentimentalize its own culture. The Greeks did not claim innocence. They knew they were newcomers, migrants, colonizers. They told stories of abduction, bride-theft, kin-murder, and traced their own origins to these violations. Their gods did the same.

Zeus abducts Europa from Phoenicia and carries her to Crete. The continent takes her name. The Greeks do not hide this. They begin their story with theft and violation of hospitality. Later, Paris abducts Helen from Sparta, and the Greeks sail to Troy to retrieve her. The myths are clear-eyed. Paris is not excused, but Greek hands are not clean. The war is just. The actors are not virtuous.

Homer’s Iliad is more sympathetic to the Trojans than to the Greeks. Hector is the noblest figure in the poem: devoted husband, protective father, defender of his city. Priam’s supplication to Achilles is the most humane moment in the epic. Achilles himself is petulant and murderous. Agamemnon is venal and incompetent. Victory does not confer virtue. Justice does not imply moral superiority.

This is the Western canon at its origin: relentlessly self-critical, suspicious of its own heroes, aware that success does not cleanse guilt. It does not claim moral purity. It preserves something more valuable: the capacity to examine its own foundations without flinching.

Athens, the city that gave us democracy and philosophy, claimed autochthony, kings born from the soil itself. Yet its defining hero, Theseus, is explicitly not born of Athenian ground. He is introduced. A foreigner granted kingship through demonstrated excellence rather than inherited blood. The myth does not resolve the contradiction. It stages it. Authority must be earned. Excellence can arrive from outside. The city that claimed the deepest roots made its defining figure a newcomer.

This willingness to complicate, to contradict, to refuse easy moral postures is what the Western canon preserves. Not innocence, but method. Not superiority, but scrutiny.

We live in an age that has forgotten this. The dominant narrative insists that Western civilization is uniquely oppressive, uniquely built on theft and violence. The irony is that this critique is only possible because the West developed the intellectual infrastructure that enables self-criticism: free speech, academic inquiry, the presumption that authority must justify itself, the suspicion of inherited power. These are not human universals. They are fragile achievements.

Thus my mythic investigations operate on two levels.

The first is polemic. It responds to contemporary amnesia by naming what has been forgotten. When land acknowledgments become absolution rituals, the polemic says this is performance, not principle. When the Western canon is dismissed as oppressor literature, the polemic says you are using its tools to dismantle the workshop that made them. When physical discipline is treated as suspect and quitting under pressure is celebrated as courage, the polemic says the ancients would not recognize these inversions.

This level is necessary. I watch as my children face indoctrination that Western civilization is uniquely evil, that competition is trauma, that discipline is oppression, that naming injustice is equivalent to refusing its benefits. The polemic provides permission to resist this narrative and evidence that it is simply wrong. We are all descended from killers and conquerors. Success was structural not moral.

But polemic alone is insufficient. It can win arguments, but it cannot transmit knowledge.

The second level is mythographic. It returns to Greek material to investigate it. It asks what structural knowledge is encoded here. What patterns recur across myths. What costs follow boundary violations regardless of intent. What conditions make excellence possible, and what makes it unsustainable. How a civilization preserves truths that cannot be reduced to propositions.

This level does not argue. It observes. It maps. It connects. Myths are treated not as diagrams; compressed records of human action encountering constraint.

When Homer shows Diomedes wounding Aphrodite, he is not offering metaphor. He is demonstrating kairos: the structural moment when impossible action becomes possible. Athena clears Diomedes’ vision and guides his strike. Intent, position, readiness, and permission align. Outside that moment, the same action would be hamartia, missing the mark, structural failure.

When we trace the line from Oeneus to Tydeus to Diomedes, we are not reading genealogy. We are watching violence inherited, refined, and finally disciplined. Carelessness generates catastrophe. Catastrophe generates escalation. Escalation disqualifies. Discipline permits refusal. Diomedes is the perfect instrument of controlled violence at Troy, then refuses further war so that Rome can be born.

When we examine Theseus, we see heroic license colliding with civic authority. Early violence restores proportion through exact reversal. Later violence forgets its limits. Each act of forgetting generates consequence. Athens honors Theseus only after his death, when his bones can be brought home and the foreign hero made autochthonous through burial.

When we study the Dioscuri, we learn that balance is not a virtue but an achievement. One twin is mortal, earned. The other divine, unearned. Together they function. When one dies, the other refuses solitary immortality and negotiates alternation. They correct what can still be corrected and withdraw before catastrophe. The Trojan War has no place for them.

These are not morals. They are structural observations. They cannot be reduced to slogans. They must be seen in pattern.

The purpose of these essays is to help recover what has been lost. What is kairos, and why does missing it constitute failure? How does violence become coherent rather than catastrophic? When must authority be earned rather than inherited? When is withdrawal wisdom rather than cowardice? Why does acknowledgment never cancel consequence?

The Western canon endures because it was founded on the capacity for self-examination. It can include critiques of itself without validating critiques that would destroy the conditions making criticism possible.

The Greeks knew about theft. They knew about colonization. They knew about power and its costs. They knew human nature does not change. What they also knew, and what we have forgotten, is that recognizing the structure does not exempt you from its operations.

Oeneus cannot avoid the boar by admitting he forgot Artemis. Theseus cannot avoid exile by acknowledging overreach. Billie Eilish cannot escape contradiction by naming the land stolen while keeping the house built on it. The acknowledgment is not action. The performance is not the principle. The structure does not care about your awareness.

This is what the myths preserve: knowledge about how the world actually works. Not moral truth, but structural truth. True the way boundaries are true.

The polemic fights to preserve access to this knowledge. The mythographic work recovers it. Both are necessary. The Greeks built the method. We inherited it. And forgetting it carries costs that no amount of acknowledgment can erase.

Γνῶθι σεαυτόν